THE HARDING FAMILY

Anthony Harding can lay claim to having invented the department store in the 1790s. He lived in Bell House with his extended family and a large number of servants.

Anthony Harding 1762-1851

Anthony Harding and his family were next to live in Bell House, moving from Streatham. Anthony Harding was born in Hoptown in Derbyshire on New Year’s Day 1762, one of four children of Anthony Harding and Elizabeth Gilman, members of the local landed gentry. Family tradition says his father ostracised him for having gone into trade but took him back when he had made himself a large fortune, On 12 November 1792, aged 30, he married Frances Cowper Ashby, also born in Derbyshire (in 1754) and possibly related to Thomas Ashby, Harding’s business associate. They married by special licence in London. Special licences were issued by the Archbishop of Canterbury and were expensive, a sign of status for the wealthier and more well-connected, who did not want the ‘vulgarity’ of a public wedding. In Pride & Prejudice, on hearing of the wealth of Elizabeth’s suitor, Mrs Bennet exclaims ‘A special licence! You must and shall be married by a special licence’. The Hardings had two children, Elizabeth born in 1793 and Frances born in 1795; Frances died aged 12 in 1807. Mrs Harding died in 1801 and Harding did not remarry.

Anthony Harding, inventor of the department store

Anthony Harding described himself as a silk mercer. In 1786 he was working for Ashby and Osborne, linen drapers on Holborn Hill or Holborn Bridge, just opposite Ely Place. In 1795 he was still living in Holborn and became a freeman of the company of musicians by redemption, meaning he paid a fee of forty-six shillings. At this time the musicians’ livery was a kind of general guild open to anyone. The fact that he chose this guild rather than the drapers suggests that perhaps he was not a trained draper, that is he had not undergone an apprenticeship. This makes his later success all the more impressive. Harding, Howell & Co.'s Grand Fashionable Magazine was located in Schomberg House on Pall Mall, a mansion originally built for one of William III’s generals, where Gainsborough had lived and which was later used as the War Office. Founded in 1789, Harding’s can be considered the first modern department store. For the first time women were able to shop on their own in public, safely and respectably. They did not have to walk along the street in public to visit different shops and so did not need a male chaperone, neither were they tied to buying the limited range of the tradesmen who visited door-to-door. They were free to browse and choose for themselves. These women were members of the newly-affluent middle-class, their good fortune buoyed by the Industrial Revolution. They went to the department store to shop, to meet their friends and to examine the latest fabrics to pass on to their dressmakers; ready-made clothing for women would not be available for another century. Drapers like Anthony Harding understood this newly emerging class of women and saw that shopping could now be a social activity and it is no coincidence that many of London’s famous department stores such as Whiteleys and John Lewis were started by drapers. The shops were designed to be as attractive and enticing as possible with large glazed windows, glass chandeliers, tall ceilings from which to hang the fabrics and large glass-fronted cases to display the merchandise.

As the premier shopping street of this nation of shopkeepers, Pall Mall was one of Georgian London’s most fashionable streets and regency ladies came here for the most fashionable textiles. It is often mentioned by Jane Austen and it is outside a shop in Pall Mall that Colonel Brandon hears of Willoughby’s engagement in Sense and Sensibility. Indeed, the most frequently mentioned item of shopping in Jane Austen’s letters is fabric for dressmaking and she would undoubtedly have known Harding’s. By 1809 it employed forty people in the store plus countless artisans all over the country supplying them with items for sale. To further attract the ‘beneficiaries of the new affluence’ Harding’s had a refreshments room on the first floor. Harding was said to be a man of ‘vision and vigour and a business genius’ and he redesigned the shop to suit his needs. The shop was on the ground floor, divided by glazed mahogany partitions into five ‘departments’: first furs and fans; secondly silks, muslins, lace and gloves; thirdly jewellery, ornamental articles in ormolu, French clocks and perfumery; fourthly millinery and dresses and lastly textiles, especially chintzes and their accessories. There was ‘no article of female attire or decoration, but what may be here procured in the first style of elegance and fashion...the present proprietors have spared neither trouble nor expense to ensure the establishment of a superiority over every other in Europe, and to render it perfectly unique in its kind’. On the first floor above the ground floor shop were workrooms with forty men and women employed by the firm. On the top floor, reached by Schomberg’s original 1698 painted staircase, was a café known as ‘Mr Cosway’s breakfast room’ where customers met for ‘wines, teas, coffee and sweetmeats’. There was a ‘noble apartment used as a shawl room’. Perhaps most importantly of all, there were toilets. Public toilets for women were rare, meaning women could not venture too far from home lest they be ‘caught short’.

Harding possessed a talent for advertising and was especially keen to reassure potential customers (or ‘families of the first rank’) that all their furnishing fabrics were made in England but that they could also supply ‘every article of foreign manufacture which there is any possibility of obtaining’. The shop had many royal customers. St James’ Palace was a short walk away and Marlborough House even had a connecting door to the shop. George III had many connections with Harding. He commissioned Harding & Howell’s to design and make the hangings for his bedroom at Kew. He asked Harding to market the cloth produced from the royal flocks of merino sheep grazed at Windsor and King George himself would bring his daughters to visit the shop. Harding would close the shop so that the royal family might browse in private, and while the king would take great interest in the goods for sale the princesses loved to go behind the counters. Queen Charlotte asked the store to design particular dress silks for her, which Harding would then cannily market under the name ‘Queen’s silk’. When the Prince of Wales asked them to design a new chintz for his bedroom at Carlton House, Harding’s marketing acumen led him to arrange for a cutting of the fabric to be pasted into every issue of Ackermann’s Repository of the Arts alongside the advertisement of their shop. He also arranged for each entrant in the newly published Debrett’s Peerage to be sent a sample of chintz and reminded of the shop’s royal patronage.

Shops were open much later than they are now, until around ten at night and in 1807 Pall Mall was the first street to be lit by gas which would make the printed chintzes and textiles look particularly ravishing. When a patent was granted for the first permanent green dye for chintz Harding secured the sole selling rights. The fabric was advertised as ‘a discovery never before offered to the public’. Harding always suggested possible linings for every fabric too, thus potentially doubling sales volumes.

In 1812, Harding employed his sister’s son, Thomas Allsop, when he arrived in London aged 17, the same age as Harding’s younger daughter. Like Harding, Allsop was the son of a Derbyshire farmer who rejected following in his father’s footsteps in favour of striking out in London. He became known as the favourite disciple of Samuel Taylor Coleridge and was also friends with such famous literary figures as Charles Lamb and William Hazlitt. Allsop became involved in radical politics, including a plot to assassinate Napoleon III, was a Chartist and was an associate of Charles Bradlaugh, the political activist and founder of the National Secular Society. He worked for Harding for at least 15 years before becoming a stockbroker.

Innovative

Anthony Harding was innovative in other ways too. London’s place as ‘the greatest and most dynamic city in the Western world’, was secure and just as Thomas Wright had sent goods out to North America so Anthony exported around the world. Although the shop covered only one third of the large Schomberg House, in 1804 Anthony Harding bought the lease for the whole building and let the other two shops; when his shop needed renovating the firm took over another part of the building, so minimising the impact on business. When they saw the demand for lace, they set up their own lace factory. They brought over a Flemish woman skilled in making French and Flemish lace and advertised for apprentice lace-makers. The Flemish expert would instruct ‘young women respectably connected and of good conduct’ in the art of lace-making, for a fee of £10 each. They also sold a hair dye which claimed to be ‘the best Dye in the universe for immediately changing red or grey hair.

Crime and Punishment

Harding was working as a shopman in draper Thomas Ashby’s shop in Holborn, where theft was a common occurrence, as it was for many shops at the time. Most stock was stored behind the counter and the shopman would have to turn his back on the customers, and possibly also climb a ladder or manoeuvre a pole, to retrieve stock, you can see this set-up in the illustration of Harding and Howell’s shop. On the morning of 3 March 1787 Harding was working in the shop, serving two women, Ann Smith and Catherine Johnson. They looked at the calicos and muslins but left without buying. Harding suspected they had stolen something as they were ‘stumbling under their petticoats’ and asked his colleague, Henry Die, to bring them back to the shop; they both came back willingly. Henry Die told the Old Bailey court that when they came back they attempted to pull some material from a table and then let the goods drop from under their own petticoats, hoping to mix them up with the dropped material but he caught them in the act. The materials that had been secreted under the women’s dresses: ‘were still warm’ said Harding, though he was scrupulous to say that he himself did not see them take the goods. Catherine Johnson, who was only 17 years old, begged to be let go and said it was the first time she had stolen anything. Ann Smith did not beg for herself but repeatedly asked that Johnson be set free and said she would pay 20 shillings for the gown. They were found guilty and, although the offence was a capital one, sentenced to transportation for seven years. Catherine and Ann were sent to Portsmouth to join the Prince of Wales, part of the ‘First Fleet’, the ships that founded Australia’s penal colony on Norfolk Island. The fleet sailed in May 1787, just two months after Catherine’s theft had occurred, and the journey was a hazardous one. Rats, lice, cockroaches, and fleas tormented the convicts, and the smell below deck was overpowering, due to overcrowding and because the bilge water was not regularly pumped away; many convicts fell sick and died. During tropical rains, the convicts could not exercise on deck as they had no change of clothes and no method of drying their wet clothing.

In Rio de Janeiro the ships were cleaned, water taken on board and repairs made. The women’s lice-infested clothing was burnt but as they had no change of clothes, they were issued with clothes made from rice sacks. The Prince of Wales arrived at Norfolk Island in January 1788. There is no mention of Catherine in the ship’s punishment books but once on Norfolk Island she was found guilty of ‘abusing a storekeeper and accusing him of theft wrongfully’ and sentenced to fifty lashes. In 1794 she is recorded as being married, with three children, and ‘living by her own means’ (most women had a supporting man’s name beside theirs) and as her transportation sentence had now expired, she could leave Norfolk Island which she did in November 1794. By 1800 she was living in Sydney and though there is no record they married, she lived for the remainder of her life with Tristram Moore, an Irish rebel himself transported for life, who became an apothecary at Sydney Hospital.

Once freed, Catherine was allowed to own property and in 1806 she bought 100 acres for £120, payable ‘in storeable wheat or cash’; a year later she transferred ownership to Tristram. She seems to have been financially successfully from the beginning of her new life in Australia, buying and selling property, including dealing with Paul Bushell, a famously successful convict of the Second Fleet. She traded property in The Rocks area of Sydney and also held beer licences. Catherine and Tristram became farmers, growing wheat and maize on around 34 acres with 18 cattle and a horse. Catherine supplemented the family income by taking in sewing. She died in 1838, aged 67, and Tristram Moore died a year later. They left their property to their younger daughter, Mary Ann.

In 1817 a Harding employee, Samuel Arnold, stole £74 in cash and £35 in promissory notes from Harding’s shop and was arrested in Bristol, having spent most of the money. He was tried at the Old Bailey and found guilty but one of the directors, who was also a relative of Anthony Harding, spoke for the firm, saying Arnold had worked for them for seven years, had been entrusted with thousands of pounds and had always ‘acted honourably’. He had recently married and his misconduct could be attributed to the malign influence of his new wife. The firm was willing to take him back into their employ. The court report tells of ‘a buzz of applause after this declaration’. The judge directed the firm to take the prisoner back and by this means Harding & Howell may have saved Arnold’s life, as such a theft could be punishable by death. Harding’s shop was also subject to ordinary acts of theft such as in 1799 when 47 year-old Mary Wilson was found guilty of stealing some black ribbon, two pair of cotton mittens and a silk handkerchief to the value of 12 shillings in total. She was sentenced to seven years transportation but died in Newgate prison two months later.

By appointment to the Queen

In December 1819 Harding & Howell moved their business to 9 Regent St, ‘opposite Carlton House’ where they were ‘quite prepared to offer a regular succession of novelty throughout the season’. This idea of novelty was important for the sale of clothes and accessories. Disposable income was increasing and the empire was providing a wider range of goods, people were beginning to buy new things even when they didn’t need them and it was important to offer new items to ensure customers kept returning to the shop. In an 1834 report from China the correspondent talks of the demand for things ‘pretty, odd and new at Howell’s or Harding’s’. Harding & Howell were obviously highly successful and in the process they secured a Royal Warrant as ‘Silk Mercer by Appointment’ to Queen Victoria.

Anthony Harding was also involved in charitable enterprises. In 1798 Harding & Howell placed an advertisement in The Times on behalf of the ‘peculiar and distressful circumstances’ of a lieutenant in the East India Company. The ex-soldier was struggling under sickness and poverty while caring for his two infant children and was threatened with ‘the cold and loathsome damp’ of a debtors’ prison. Donations were to be left at Harding & Howell’s on Pall Mall.

On 11 August 1821 Anthony’s daughter, Elizabeth, married Thomas Scholes Withington in Brighton. He was a cotton twist dealer who was born in Manchester and educated at Manchester Grammar School. The couple moved around the country, no doubt on business connected to the cotton mills in the north of England. The Withingtons’ four eldest children, Alice, Frances, Arthur and Florence were born in Liverpool, the next two, Augusta and Allan, were born in Grasmere in the Lake District while their youngest, Elizabeth, was born at Bell House, where the family lived with Anthony Harding from 1832 onwards.

At home at Bell House

In 1832 Anthony bought a new lease on Bell House which obliged him to contribute to the cost of lighting Dulwich village. At the sme time the two cottages in the grounds built by Thomas Wright were excluded from the lease and rented instead to Samuel J. Nail. He knocked them into one and after the publication in 1836 of Charles Dickens' 'Pickwick Papers' they became known as Pickwick Cottage, though the official name of the property was Trewyn. Joseph Romilly, whose family lived at The Willows on Dulwich Common, records in his diary on 2 April 1833: ‘called with Lucy on Mrs Withington (born Harding) at Bell House, found there at 12 o clock a Daniel Lambert at lunch (suppose it to be Mr Withington). Civilly received by Mrs Withington, she will state our Blencowe case to her father’. The Blencowe case concerned Maria Blencowe, a protegee of Lucy Romilly, who was a candidate for admission to a charitable institution.

Calls were an essential part of social networking. Ladies often had a particular ‘at home’ day where they received callers for tea and cake. People did not stay long and it was not rude to say you were ‘not at home’, the convention was that the caller would simply leave a card. All calls and cards had to be returned however and daughters were expected to accompany their mothers from when they were old enough until their marriage when they would commence their own round of at-homes.

A full house

In 1841 the population of Dulwich was only 1,904 people though Bell House was a large household at the time with Anthony, still described as a silk mercer, though he is now 75, his daughter Elizabeth and her children Alice, 17, Frances, 16, Florence, 13, Augusta, 11 and Elizabeth, 7. The servants included Sophia Hegley, 25, the children’s governess, Sarah Gager, 45, the cook, Elizabeth Idgwick 40, Maria Chapman 25, Jane Cane 20, Jane Hanley 25 and Ann Townsend 20 and a manservant called Thomas Shiels. There were also three visitors on the 1841 census - Thomas and Ann Procter and Caroline Shaw - described as having independent means. In the coach house (now known as the Lodge, lived George their coachman, his wife Hannah and their daughter Harriet.

There would also have been ‘daily’ servants like gardeners or ‘charwomen’, who did not live in but came to work each day or to help if the family were entertaining. The lives of these figures are even harder to recover than those of the live-in servants as we have no names or particular duties and they were at the bottom of the domestic pecking order. Butlers were at the top of the servant hierarchy and were known by their surname. Cooks were given the courtesy title of ‘Mrs’ even if unmarried. Parlourmaids were the most senior maids and were addressed by their surnames while other maids were called by their Christian names. Most of the Harding servants came from London or the home counties as was usual at this time. Often the best way to get a reliable and trustworthy maid was through the recommendation of friends or acquaintances at church. Later, servants would come from farther afield, either travelling with a family when they moved to London or obliged to leave the countryside because of mechanisation or agricultural depression. The nature of service was also changing at this time. No longer considered part of the family, servants were now exclusively working-class and usually female, with a heavy workload and expected to be neither seen nor heard. At this time a large extension was added to Bell House for servants’ quarters. Several of the servants appear in more than one census, meaning they were with the family for at least ten years and one, Jane Cane, stayed with the family for more than 30 years and was photographed with Florence Withington, one of Anthony Harding’s granddaughters, showing how much she was valued by the family.

In the 1851 Census, Anthony Harding was now 89 years old and still described as a silk mercer, His granddaughters Frances, 26, Florence, 23, and Augusta, 21, are all described as fund holders, that is they had an independent income. His granddaughter Elizabeth, 17 was still in education. His grandson Arthur, 24, was a silk mercer and another grandson Allan, 19, was studying engineering. Sarah Gager, the cook was still here, as was Mary Cane, 34, the house maid. The lady’s maid was Ann Allison, 31, Sophia Church, 24, was the under housemaid and Mary Ann Baker, 17, was the kitchen maid.

Peterloo

Elizabeth Harding’s husband, Thomas Scholes Withington, played a significant part in the tragic events of the 1819 Peterloo Massacre in Manchester when several people were killed and hundreds injured after the cavalry charged a group protesting for parliamentary reform. In 1816 Withington had been elected as a constable for the manor of Manchester, and in 1817 he was elected Borough Reeve, the chief officer of the town and equivalent to mayor. In 1818 he took a petition to the Chancellor of the Exchequer, protesting against the high duty on printed cottons, stressing the harmful effects or ‘lamentable and greatly increasing calamities’ on the workers. The duty was not in fact abolished until 1831.

On 16 August 1819, the day of the massacre, he carried the request for help in keeping the peace from the chairman of magistrates to the commander of the cavalry. The magistrates, concerned about the large crowd that had gathered to hear the radical speaker Henry Hunt in St. Peter’s Fields, decided to arrest Hunt and break up the meeting. Withington ‘read the Riot Act’, the law that had to be read out before an unlawful gathering could be broken up, and the local volunteer forces of the Manchester and Salford Yeomanry were called upon to help disperse the crowd. The military groups made the fatal mistake of charging from three different directions leaving the crowd nowhere to escape, with inevitable casualties. The massacre was given the name Peterloo in ironic reference to Waterloo, which had taken place four years earlier. After the massacre the magistrates ordered the pubs to be closed and Withington was employed to help clear them. A crowd collected and ‘Mr Withington, anxious to disperse the crowd as mildly as possible, remonstrated with them …but had his coat torn from his back, his waistcoat likewise’. However, he stuck ‘firmly and resolutely’ to his task and took Thomas Mellor, the man who had assaulted him by tearing his clothes, into custody. Mellor was held in custody from 16 August until 27 January of the following year. At the trial Withington asked for clemency for Mellor since ‘sufficient punishment’ had been suffered. Mellor was fined 6s 8d and bound over to keep the peace. He was asked to pledge £10 plus £10 from a third party, a hefty punishment given the amount of time he had already spent in prison.

It was said that Withington refused a knighthood but accepted a silver cup (which passed to his son Arthur who emigrated to America). He was allegedly known as ‘Three Bottle Borough Reeve’ from his ability to drink that amount of port, an accolade he shared with Pitt the Younger. Withington died on 30 August 1838, aged 47; his wife, Elizabeth, died on Christmas Eve 1853. Of their children (Anthony Harding’s grandchildren):

Alice married Alfred Eccles, a doctor from Tunbridge Wells in 1848. They had one son who died at six months old. Alice herself died in 1852, aged 28.

Frances Withington married the Revd Stephen Poyntz Denning (son of the portrait painter and curator of Dulwich Picture Gallery) in 1852 but their life was full of tragedy: all four of their children died before they reached the age of eight and Stephen himself died aged 40.

Florence Withington married the Revd Herbert Morse in 1851. They had five children but Florence was widowed seven years after her wedding, in 1858.

Elizabeth Caroline Withington married the Revd William Henry Helm, headmaster of King Edward's School, Worcester, in 1858 but was widowed six months later and their son was born after his father’s death.

At first Allan Withington worked at Harding’s with his grandfather but then became an engineer. He married Sarah Cooper in 1859 (they were second cousins) and they emigrated to the US, then Argentina but she died within four years of their marriage. Allan later settled down as a farmer in Sussex.

Arthur Harding Withington followed in his grandfather’s footsteps and became a silk mercer. He married Emma Marzetti in 1853 and they emigrated to the US with their 2-year-old son, buying a farm in Baraboo, Wisconsin. He was very involved in the life of the church there and was church warden for many years. His wife’s sister Louise, and her husband William Gowan (whose brother later lived in Bell House) came out from England to join them, buying a neighbouring farm. Arthur died in Baraboo in 1873. His son, Arthur Claude, became a travelling salesman in the US, enjoying ‘a full measure of success’ and also ‘contributing materially to the welfare of Baraboo along civic, educational and moral lines’. He took a full part in the community life of Baraboo, founding the public library and creating a beautiful garden for the town as well as being church warden. There is a tablet to his memory in Baraboo Library.

It is always difficult to research the lives of servants in a house such as Bell House, they often move around a lot, their ages and even their names are not always accurately recorded but we are lucky in one servant, Jane Cane, who served the Harding family for over 30 years and clearly became important to them. In 1841 and in 1851 she is a general servant at Bell House. In 1861 she is a children’s nurse and is with Elizabeth Caroline Helm, her son, William Henry Helm and her niece, Florence Denning in Hampshire where they are visiting relatives. In 1871 she is in Shanklin, Isle of Wight, a lady’s maid, living with the Morses, Elizabeth Caroline Helm, Willian Henry Helm and Frances Denning. She died in 1881 in Islington. We even have a photograph of her with one of her young charges, Florrie Denning, on her knee.

Anthony Harding himself died on 5 August 1851 in his 90th year and was buried in the crypt at St Leonard’s on Streatham High Road. He was said to never get drunk but lost the use of his legs after six bottles or so, and had a special chair made so that the footmen could carry him up to bed. His coffin stood against the wall behind his chair in the dining room in Bell House before his burial. He was said to have been the last man in London to wear a queue (a kind of ponytail or braid often added to Georgian wigs). His shop lasted for a few years after his death but then closed and the building was taken over by the War Office in 1859.

sharon@bellhouse.co.uk

Anthony Harding

Harding & Howell's store, in Ackerman's Repository

Harding & Howell's on Pall Mall

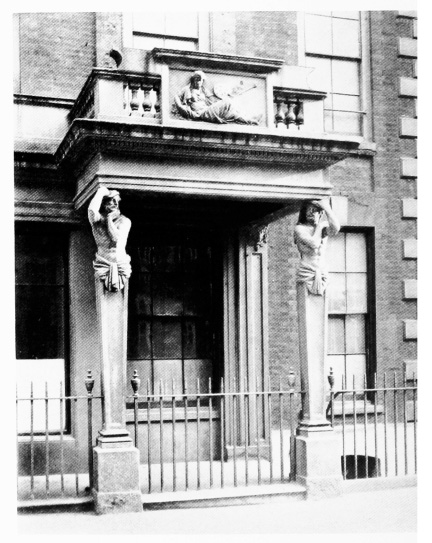

Schomberg House today

Harding added this porch

View from Mr Cosway's breakfast room, painted by William Hodges

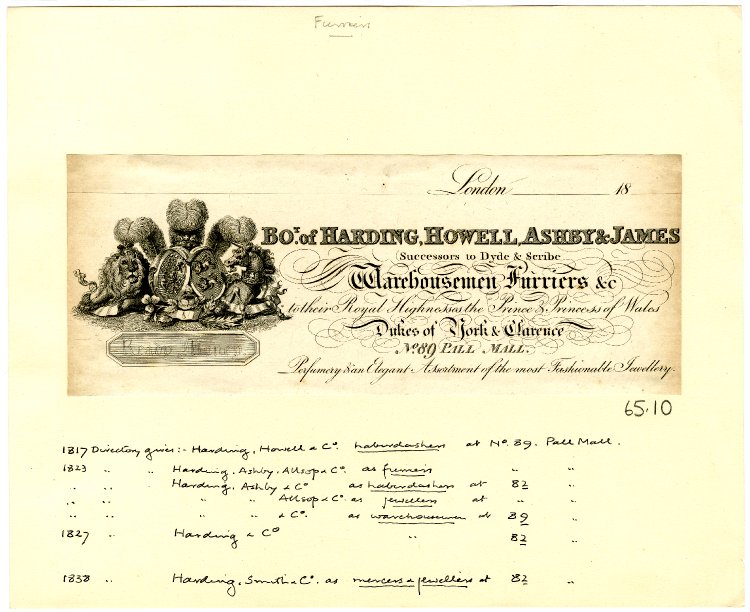

Harding & Howell letterhead

Samples of chintz produced for the Prince of Wales added to Harding adverts

Samples distributed with Ackermann's Repository showing 'permanent green' chintz

Page from Joseph Romilly's diary, 2 April, 1833

Elizabeth Harding Withington, Anthony Harding's daughter

Elizabeth Harding Withington, taken in 1849 while she lived at Bell House

Peterloo Massacre, 1819

Alice Withington Eccles, taken in 1849

Frances Withington, taken in 1849 when she lived in Bell House

Stephen Poyntz Denning, husband of Frances Withington

Florence Withington, taken in 1849 when she lived in Bell House

Elizabeth Caroline Withington, taken in 1849 when she lived in Bell House

William Henry Helm, husband of Elizabeth Caroline Withington

Elizabeth Withington Helm, Harding's granddaughter, who lived with him at Bell House

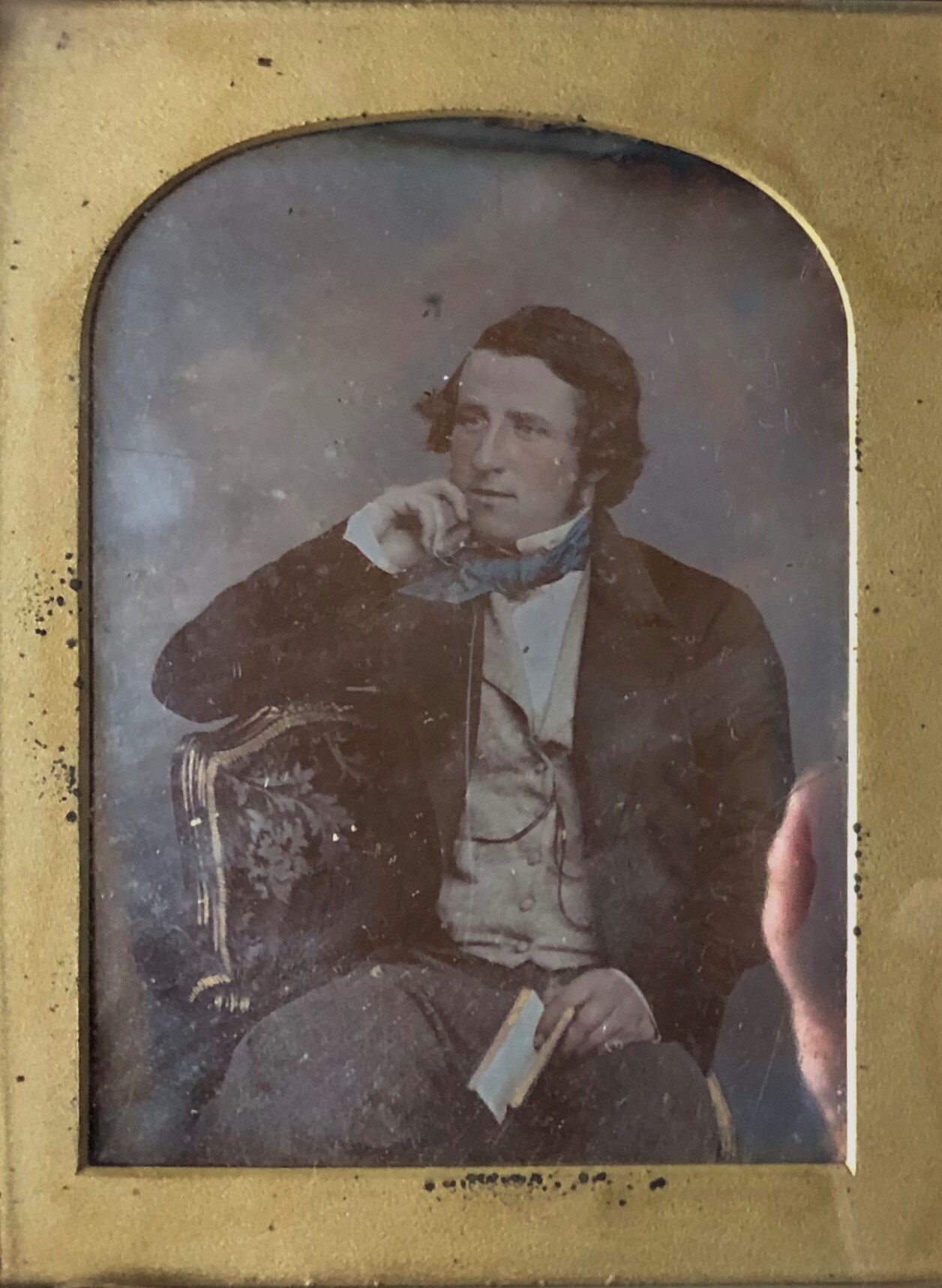

Allan Withington, taken in 1849 when he lived in Bell House

Arthur Harding Withington, taken in 1849 when he lived in Bell House

Jane Cane and Florrie Denning, taken in 1860.

Sketch of Bell House made by one of Anthony Harding's family